Share this post

The Limits of Growth

September, 2020

Since the start of the year, one area of the market that has delivered phenomenal returns to investors, in spite of a global pandemic, poor economic growth and rising geopolitical tensions is compounder type businesses and companies claiming to be compounders.

What exactly is a compounder business? They have three main characteristics. First, they tend to be growing rapidly. Second, they have a long runway for growth and re-investment, so they are not at the end of the S-curve used in describing growth companies. Finally, they are capital light and tend to use operational leverage, meaning that a small increase in revenue leads to a much larger increase in profits. These businesses enjoy increasing returns to scale. Technology companies are often compounders.

So, if these businesses are all so wonderful, why don’t we simply invest in them and let the power of long-term compounding growth work its magic?

Regardless of how wonderful a business is, valuations do matter. Most investors use the late 90s dotcom and telecoms bubble as an analogue for what is happening now. This is not correct. At least, not entirely correct. In the late 90s, you had speculative businesses trading at speculative prices. Today, you mostly have financially sound businesses trading at speculative prices. There are some local bubbles of speculative companies trading at speculative prices, but these are not the majority.

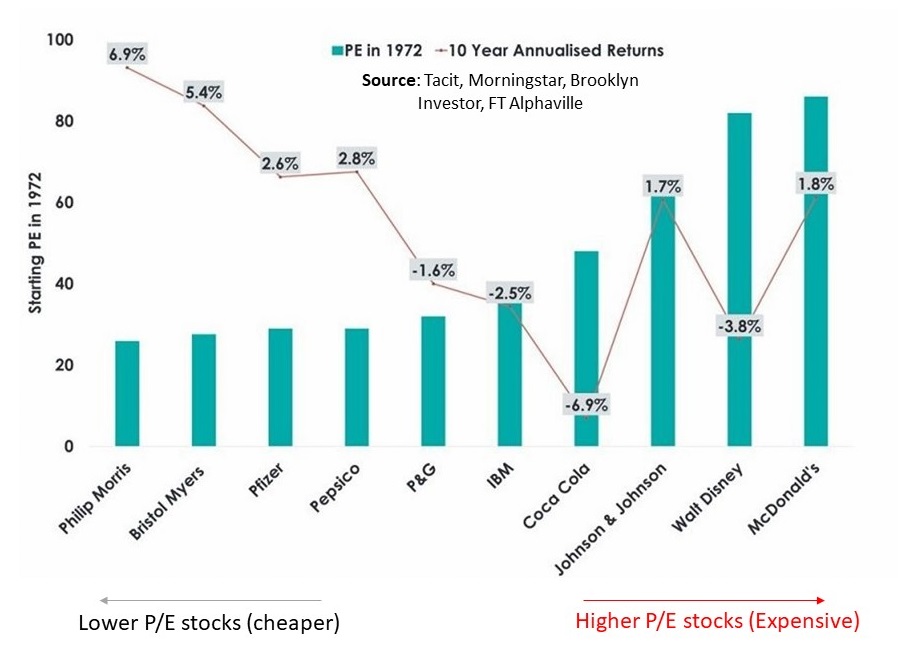

A better analogue to what is happening today is what happened in the early 70s in corporate America. The compounders of the day, or “blue chips” as they were called back then, were trading at lofty valuations. Investors buying blue chip companies at peak valuations of 1972 suffered 10 years of poor returns as shown in the Figure below.

This is not supposed to be a detailed statistical study, but one can eyeball the general trend – higher valuations at the time of purchase led to lower future returns.

These are all nominal returns, so even the relatively impressive return of 6.9% annualised over the next 10 years by Philip Morris was actually in negative territory because inflation during this period averaged 8%.

Now, over the longer term, these companies did fine. Some failed, like Polaroid (not included in the chart). But most of them thrived. Let us look at the worst performing stock in this group, Coca-Cola, as an example. Investors buying shares of Coca-Cola in 1972 paid a price to earnings (P/E) multiple of 48. Over the next 10 years from 1972, nominal returns were -6.9% annualised. Over the next 20 years from 1972, nominal returns were almost 12% annualised. So over the very long term, you were not penalised for overpaying since the long-term returns of the S&P 500 are about 10% annualised.

However, almost all investors lack the stoic poise needed to do nothing and nurse a 6.9% loss of investment, every year, for 10 years. At this rate, almost half of your investment has disappeared after 10 years. In real terms, it is much more than that, but we shall spare you the anxiety. More perplexing is that the company itself was doing fine over this period. Between 1972-1982, Coca-Cola was rapidly growing revenues, launched the “I’d like to buy the world a coke” advert – one of the most famous television commercials in history, started its sponsorship deal with FIFA, expanded to China – a rapidly growing market with a large population and introduced Diet Coke which became a wildly popular beverage. Throughout this time, while so many wonderful things were happening for the company, the share price went down.

This is the risk with overpaying for a stock, regardless of how spotless its financials or how wonderful its unit economics are. Lofty earnings multiples can contract, and the price people are willing to pay for every stream of earnings can fall.

At Tacit, we continue to focus on this risk of earnings multiples contracting. This is a risk many of our peers and retail investors may not be taking seriously as the share prices of today’s compounder type companies only go up. But they should because history often repeats itself and it can be a harsh tutor.