Share this post

Navigating a Crisis

April, 2020

We have often written about the stabiliser and growth approach used in our strategies. The growth assets, as the name implies, generate the majority of the growth in investment returns. This includes shares in companies, high yield bonds and emerging market debt.

The stabiliser part of the portfolio is less exciting. Stabilisers exist for one reason and one reason alone – to reduce losses during periods of distress. The math behind this is very important in understanding why Tacit’s strategies have performed the way they have during this period and, more importantly, are a guide to how they will perform during the recovery.

The most important feature of a stabiliser asset is that it has some measure of predictability in performance during periods of distress. For example, some of our peers’ class high yield bonds as stabilisers. This thinking is of course flawed because during periods of distress like we are currently facing, high yield spreads increase, meaning bond prices have fallen. A stabiliser asset cannot lose its value right when you need it the most.

So our first edge at Tacit is the correct classification of stabiliser and non-stabiliser assets. Stabilisers must have a negative or zero correlation to growth assets, particularly equity markets, during periods of distress. Our main stabiliser assets are cash, which keeps its nominal value during periods of distress, investment grade sovereign bonds, which correlate negatively to equities, and gold.

Nathan Rothchild said he only knew two men who could value gold – a clerk in the Banque de Paris and a Director in the Bank of England. Unfortunately, they both disagreed on its value. This is the difficulty with “investing” in gold. Its true value is opaque but its job in a portfolio is clear. It is cash 2.0 because it correlates negatively to equities during extreme events and keeps its real value much better than paper money ever could. This is why we have some gold in all of our strategies – as insurance against the unknown and, more importantly, as a proxy for cash.

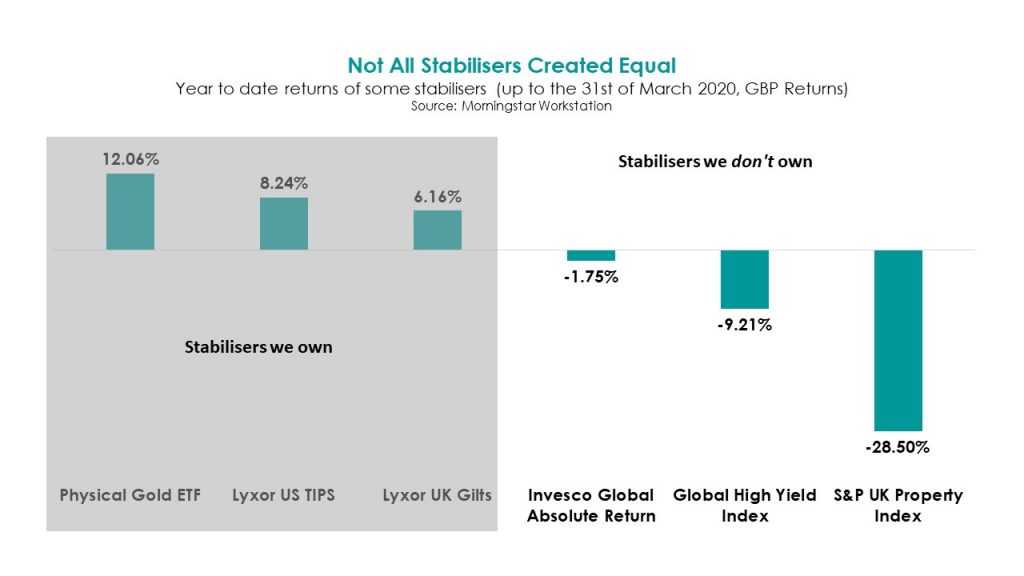

Our second edge is less about what we do, but what we don’t do. We have often mentioned that the avoidance of harm is the most important risk management principle. This is boring and may seem trite but nevertheless holds true. Some of our peers use property funds and absolute return funds as stabilisers. This is flawed investing thinking in our opinion and the data once again supports our intuition.

Property funds and absolute return funds have once again, in aggregate, failed to provide protection when needed the most.

The right mix of stabilisers can also act as an option on lower equity prices. If you own a basket of stabiliser assets that increase in value by 10% during a crisis (which is the average increase from the stabilisers we own shown in the Figure above) and equity prices fall by 30%, as they have in most developed markets, then your buying power of discounted equities has increased by 57%. On the other hand, owning a basket of stabilisers that, on average, fall by about 10% (which is the average decline in value for stabilisers we don’t own but which some of our peers will own), your buying power increases by only 29%.

Finally, being able to sell a stabiliser and buy cheaper equities is obviously very important. Some of the faux stabiliser assets like hedge funds and property funds often can’t be sold at all during periods of distress.