Share this post

History rhymes

April, 2022

Russia’s incursion into Ukraine has raised a multiplicity of complex ethical, political, social, and economic issues which elicit different explanations and responses, depending on the perspective from which you begin. We in the UK are largely influenced by what might be termed a ‘developed world’ perspective, which might crudely be characterised as democratic, broadly liberal, and governed by the checks and balances of what we term ‘civil society’. Another characterisation of the developed world could be the ‘Atlantic Alliance’, which in itself may explain a failure to recognise the significance of nations for whom the Pacific is the unifying sea mass, and those nations locked in land masses with no significant coastal boundary. Whichever way we characterise ourselves, 80% of the world’s population lives outside the ‘developed world’.

If we thought the world had moved beyond territorial conquest in preference for mercantilist warfare, with corporations slugging it out for global dominance, the bellicose actions of Russia in the last six weeks have, regrettably, brought us back to the battlefield. Setting aside any explanations rooted in the personality of individuals, we have been considering how this unanticipated battle for territory can make sense. An emerging thought is that in an era in which the exploitation of natural resources to feed an unsustainable appetite for consumption is creating scarcity, control of the most elemental components of human survival will become more important than the peripheral by-products of a highly developed consumerist culture.

To illustrate the tenants of this speculation, we have gone back over 100 years to an article written by the eminent lecturer and British MP, Halford J. Mackinder.

In 1904, he wrote an essay that changed how politicians and military men viewed the world. It was a perception that influenced Hitler to send his panzers east against Soviet Russia. It was a perception that, only recently, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, had seemed all too relevant – relevant enough to be part of the intellectual underpinnings for foreign policy in the West. The theory that had so influenced nearly three generations of strategists is called the Heartland Theory.

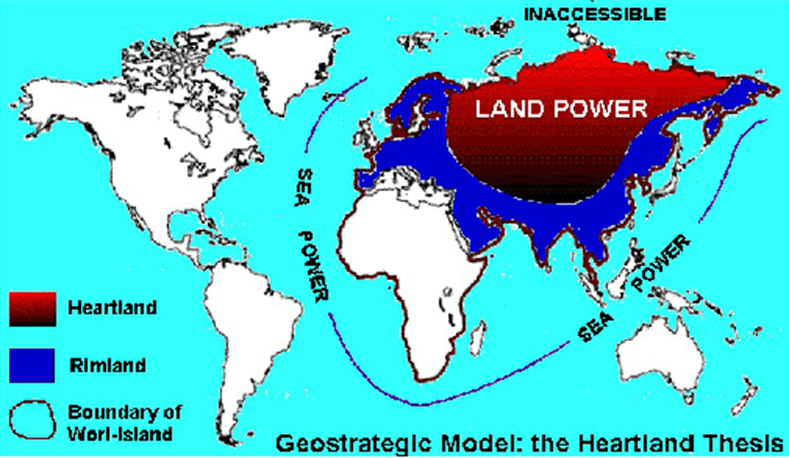

In a nutshell, Mackinder saw history as a struggle between land-based and sea-based powers. He saw that the world had become a “closed” system, with no new lands left for the European powers to discover, to conquer, and to fight over without affecting events elsewhere. Sea and land-based powers would then struggle for dominance of the world, and the victor would be in a position to set up a world empire.

Mackinder’s theory stated: “who rules Eastern Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island, who rules the World-Island commands the World.”

In practical terms, this theory points to a struggle for the control of Eastern Europe (including European Russia) by the land powers. The sea powers would then have to fight the victor to prevent control of the Euro-Asian-African landmass and ultimately the world.

In a post Imperialist world theory such as this have not been relevant to consider but it should remind us all that there are aspects of global political and economic thinking that none of us can ever fully understand at any point in time. This theory partly explains the current concerns in the developed world regarding China and Taiwan.

As investment managers, we strive to separate our personal opinion from our analytical evaluation of the conditions which we are required to evaluate, but there is often benefit in looking at present circumstances through the lens of another era. Using Mackinder’s framework, we can see that Europe is using economic sanctions against Russia as a way to control the economic power of the Heartland and preserve the control of the Sea Powers. Russia is using its natural resources to counteract this. Couched in other terminology, we can see a conflict between dominance over natural resources (including the agricultural potential of Ukraine) and mercantilism (which for Russia translates into a seaboard through which it can export its natural resources eastward as much as the Nordstream pipeline gave it access westward).