Share this post

Estimating Fair Value

April, 2020

We are often reminded that financial markets can be volatile and erratic, and none more so at present than the oil market which briefly traded below zero last week. Imagine turning up at your local garage and being paid by the garage to fill up and drive on.

Oil is by no means the only asset to trade below zero; Northern European and Japanese bonds have traded through zero for some time and indeed, the key ECB deposit rate is currently minus 0.5%. The Bank of England rate is as close to zero as to be immaterial.

Joining the zero-yield club, following official interventions, is much of the financial and insurance sector where dividend yields have been cut to zero. Many non-financial firms have also ceased paying dividends in an effort to conserve cash. Most businesspeople will tell you that it is not profitability that kills business, it is cashflow; the lifeblood of business which is simply not flowing at the moment.

The market which is of most importance to us as investors is the stock market. So, when one of the key valuation metrics has disappeared how is it possible to estimate fair value on companies and company shares?

In some respects, it is, of course, not possible. There is so little transparency surrounding the outcome of the pandemic that any view of the future requires a myriad of assumptions that may or may not come to pass.

On the other hand, this is not the first crisis that the economy has endured and the needs of 66 million people in the UK will not evaporate as a result of an itinerant pathogen.

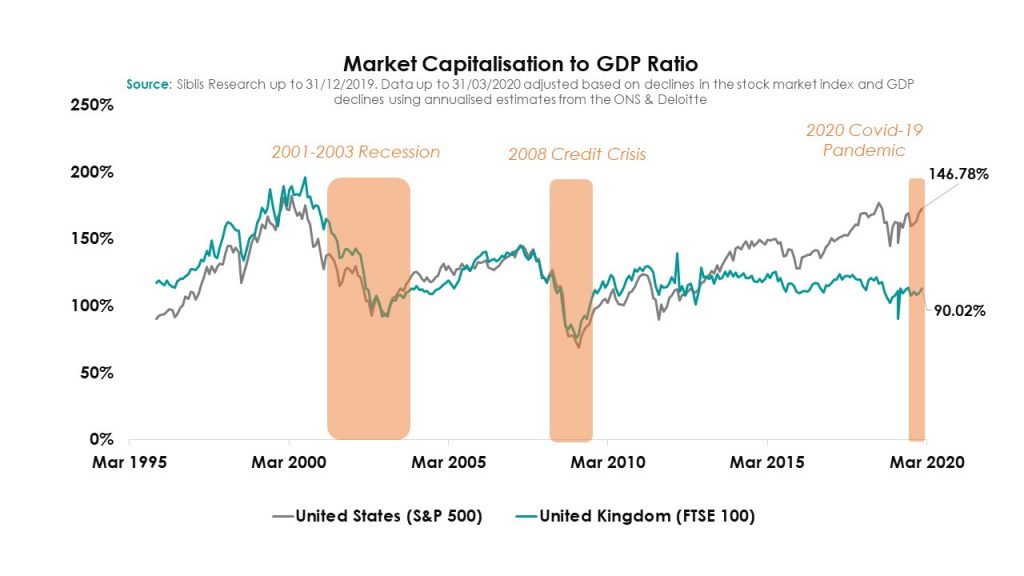

One of the models we use in the UK to estimate excess or under-valuation of equities relative to the underlying economy is to track the progress of the stock market against nominal GDP using the FT100 as a proxy.

Since 1984, the birth of the FTSE as we now know it, as you would expect, the stock market has broadly moved in step with economic growth, oscillating between periods of greater or lesser dearness/cheapness relative to the underlying economy.

Interestingly, despite the global financial crash in 2008, the period of dangerously high over-valuation was in the 1990s during the era of the Telecoms, Media and Tech bubble (TMT). It took the stock market twenty years to work off the excess of the over-valuation reached in that period. Even so, when the decline came in 2000-2003, the market didn’t trade through trend nominal GDP, in fact, it bounced off that trend until it peaked again in 2007.

During the depths of the 2008-10 financial crisis period, the market only traded through trend GDP for a very short period of a few weeks before regaining its composure and beginning its recovery.

Since 1984, it has been very rare for the market to trade below trend nominal GDP for any length of time. However, the picture more recently has been very different for the UK and US (two extremes since 2008).

In the recent decline, the UK stock market plummeted through trend GDP and has yet to rebound. In other words, the market is discounting the most serious damage to economy since the FTSE started back in 1984.

That is plausible but what does our model tell us about valuations?

1. The model suggests that to justify the recent dramatic falls in the UK index, nominal GDP would have to fall by about 35%. To put that in context, that would be of the same order of magnitude as the Great Depression but the fall in GDP then took three years to occur; from 1930 to 1933.

2. The ONS (Office for National Statistics) estimates that the GDP decline in the first quarter of 2020 was minus 1.5% which annualises at minus 6.1%. That is slightly worse than the outcome in 2008-10 but on our model a GDP decline of that magnitude would put fair value on the FTSE between 7142 and 7687. Applying a discount to that to reflect the uncertainty and fear prevalent in the market currently and a FTSE level of around 6500 looks fair. In other words, not a raging bull market, but reasonable upside from here.

Of course, this is only a model. Nevertheless, we should remember that though “all models are wrong”, some are useful.

Given modern medical advances and a century of technological and economic progress, discounting a rerun of the 1930s does look implausible. Therefore, at the recent bottom, the market was probably over-reacting and trading below what might be regarded by longer-term investors as fair-value.